Runaway Girl: Escaping Life on the Streets One Helping Hand at a Time by Carissa Phelps

Runaway Girl: Escaping Life on the Streets One Helping Hand at a Time by Carissa Phelps

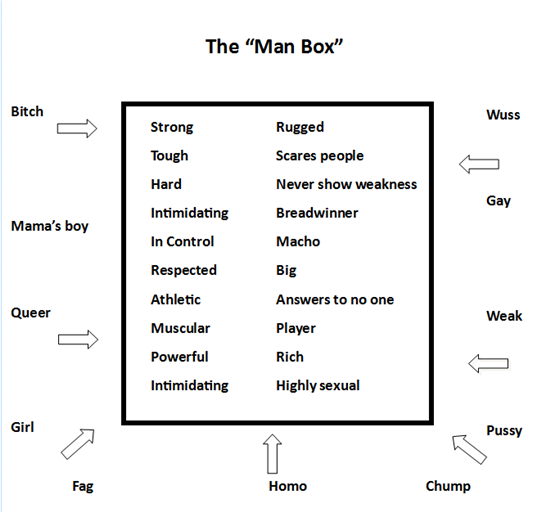

Runaway Girl is the memoir of Carissa Phelps, a survivor of domestic minor sex trafficking. This well-written tale does an excellent job of defining prostitution as an institution held in place by brutality and violence. Through the account of her own journey, Phelps shows the connection between the devaluing of girls in families, in schools, in our communities and in religious doctrine and the exploitation of girls and women by pimps. As with most testimony by survivors, Carissa Phelps’ story shows how pimps take advantage of young girls who are the most vulnerable “recruiting” them through emotional manipulation and finally use violence (most often rape) to reinforce a sexual ownership. When I finished the book, I realized that we have to get as good at recognizing when girls are in pain as pimps are. Somehow, we have to stop supplying these men with an eager supply of victims.

Carissa grew up in a very large, blended family. There was a step father who was violent and a mother who because of her own challenges was unable to protect her children from harm. The first in a line of spiritual angels in Carissa’s life was a grandmother who taught her how to pray. In spite of all that transpired in Carissa’s life, she always felt a connection to God through prayer. As she became a preteen, Carissa started to feel uncomfortable at home because of her step father’s sexual overtones. In an effort to move away from danger, she tries to move in with a brother and her biological father – and is threatened by her brother. Beginning to feel like nowhere was safe, she begins to run away a lot.

I don’t think I have ever appreciated how hard life is on the street for a young person until I read this book. For a young girl of twelve, Carissa does the best she can moving from different friends’ houses, but she eventually runs into trouble. She becomes sexually active with older men initially for survival. She gets caught a couple times for shoplifting and gets good at running away from detention centers and group homes.

One time when Carissa is on the street with no where to go, a car pulls up and a man tells her to get in. The man takes her to a hotel room, rapes her and then leaves her – promising to come back in the morning. As Carissa tries to escape she meets a pregnant sex worker who has been badly abused and takes her back to the hotel. The pregnant woman’s pimp arrives on the scene and convinces Carissa to “help them out” by turning tricks. The older woman teaches Carissa what she needs to know and accompanies her the first time. Carissa experiences dissociation – a temporary break from consciousness that happens when a person experiences trauma. After the first time, the experience isn’t as scary but it never gets easier. The couple always take all of her money. She is also forced to do drugs with them.

The pimp sets Carissa up for a gang rape and later brutally rapes her while choking her with a belt around her neck. A while ago, I read Girls Like Us the narrative written by Rachel LLoyd – a survivor of sex trafficking who has started the organization GEMS in New York City. The brutality of the pimps in both stories has had a lasting effect on me. The level of violence these young girls experience is unfathomable. I want to understand more about why these men who are older, physically larger, armed and have a psychological hold over their victims are so violent. Perhaps the question is naïve, but I would like to understand.

The effects of life on the streets included feelings of shame and problems with alcohol and drug use. Carissa explains feeling like a stranger in her own body. She felt like she didn’t deserve love – and attempted to derail her relationships with men. She was later diagnosed with PTSD, and found out later in life that a Pelvic Inflammatory Disease had been left untreated.

In spite of all her hardships, Carissa’s own determination as well as a host of angels created opportunity after opportunity leading her out of a dangerous path. An alternative high school gave her college credits. She was able to graduate from college and then Law School. Later, she earned an MBA. She started speaking about her experience to young people who were in her same position and to policy makers. She was involved in community activism and created a documentary about sex trafficking, Finally, she has written her book, which is a remarkable resource for those of us who are trying to understand more about the topic and how we can make a difference.

Runaway Girl is often heartbreaking to read, but all along you are rooting for this young girl who has been through so much and are impressed by this woman who has survived and can talk about it all. Carissa points out that most people who survive sex trafficking are yearning for opportunities to give back and help other young girls. The book ends with a thorough resource guide for survivors and practitioners.

The book is a testament to hope and the value of God’s grace.

Click here if you would like to support The Dawn Project: http://www.gofundme.com/3arrqo